About a year ago, I was having dinner at a Vietnamese restaurant in Sanlitun, a trendy part of central Beijing with shopping malls packed with international brands. With me were Italian and French friends who'd come to China on a government scholarship to study filmmaking.

Our perfectly ordinary encounter would have been implausible forty years ago. Only a tiny number of people from overseas were living in China then. The country's domestic film industry took in $4.6 billion at the box office last year, but in the 1970s you wouldn't have come here to study film, as the industry was stagnant and little better than dead. And although today China and Vietnam are trading partners to the tune of $100 billion dollars last year, in 1979 they would faceoff on the battlefield.

The extraordinary changes that have taken place in the lives of the two people we met that night were due in no small part to the determination of another Sichuan local, Deng Xiaoping. He led the push to bring a decade of nationwide turmoil to an end with a five-day meeting of the Communist Party of China (CPC) at the Jingxi Hotel in western Beijing on December 22, 1978. The communique that followed the meeting spoke of a shift to "socialist modernization", "the rapid development of production", and "acting in accordance with economic laws and attaching importance to the role of the law of value." It was the start of China's policy of reform and opening up.

When we talk about innovation in China today, we talk about things like high-speed rail, artificial intelligence, and 5G networks. But equally transformational were the innovative solutions people found to the challenges facing them at the start of the reform period. For example, villages had to work out how to divide their collective property. As MIT economics Professor Huang Yasheng wrote, "some of the assets, such as plow animals or heavy-duty equipment, either were too expensive to be acquired by individual households or were indivisible assets – a donkey cannot be divided in two." So they turned them into shares the villagers could buy and trade, and the capital this generated allowed some of them to leave farming behind and start their own businesses. This led to a boom in small manufacturers, some of which grew into firms like the whitegoods and electronics giants Kelon and Midea, which bloomed in the Guangdong countryside.

Securitizing a donkey might not sound very transformational. But it's hard to get across how desperately poor China was back then. The World Bank publishes historical GDP figures in current U.S. dollars that helps illustrate the point. In 1978 the per capita GDP in the United States was $10,587; in Latin America and the Carribean it was $1,575; in the Middle East and North Africa it was $1,366; in Sub-Saharan Africa it was $495.

And in China? In 1978, the per capita GDP was $156 per person. Last year, it was $8,826. It is 57 times higher now than what it was then. In that time, it grew sixfold in the United States and Latin America and the Caribean, fivefold in the Middle East and North Africa, and three-fold in Sub-Saharan Africa.

In 1978, for every 1,000 children born in China, 53 would die in infancy, according to an estimate by the World Health Organization. That figure has plunged to just seven. A child born today can expect to live a full decade longer than one born 40 years ago. And they will likely grow up to be much better educated: Half the kids in China didn't go to secondary school in 1978, but in 2013 enrolment was at 95 percent. And in the mid-1980s one-third of the population was illiterate; at the start of this decade it was around 5 percent.

Have the 40 years of reform and opening up been plain sailing? Of course not.

And China has an uphill battle ahead as it works to address challenges that include an aging population, reforming the finance sector to provide more support to private businesses, and preparing state-owned enterprises so they are better prepared to face the challenges that accompany competing in an increasingly open and globalized marketplace. These are tough challenges for a developing country. China is far more developed than it was 40 years ago, but there's still a long way to go. The country has 998 million people of working age but only around 6 percent are expected to pay tax next year because they earned more than 5,000 yuan a month – about $8,500 a year. China is home to the world's second-largest economy, and it's increasingly prosperous, but it's not yet rich.

These challenges might seem daunting, perhaps even insurmountable at first glance. But if, in 1978, you'd described the China of today to the elderly mother from Sichuan she'd have perhaps thought you were mad. The last four decades have bought tremendous change to the lives of people across China, and the journey of change is far from over. But the Chinese people have shown a tremendous capacity to study, to work, to start businesses, and to innovate. The achievements of the past 40 years was not a miracle; it was the hard work of more than a billion people that made it happen.

Note: Carl Benjaminsen is an editor and radio host at China Radio International, China Media Group.

Captions:

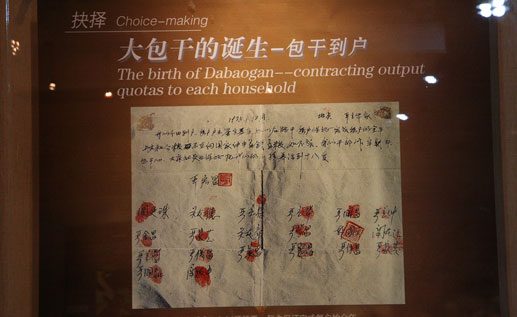

1: A photo of the pact signed by the villagers in Xiaogang, Anhui Province in 1978. [Photo: VCG]

2: A photo of Xiaogang Village before 1978. [Photo: VCG]

3: The villagers who signed the pact in 1978 pose for a photo at the entrance to Xiaogang Village in 2018. [Photo: VCG]